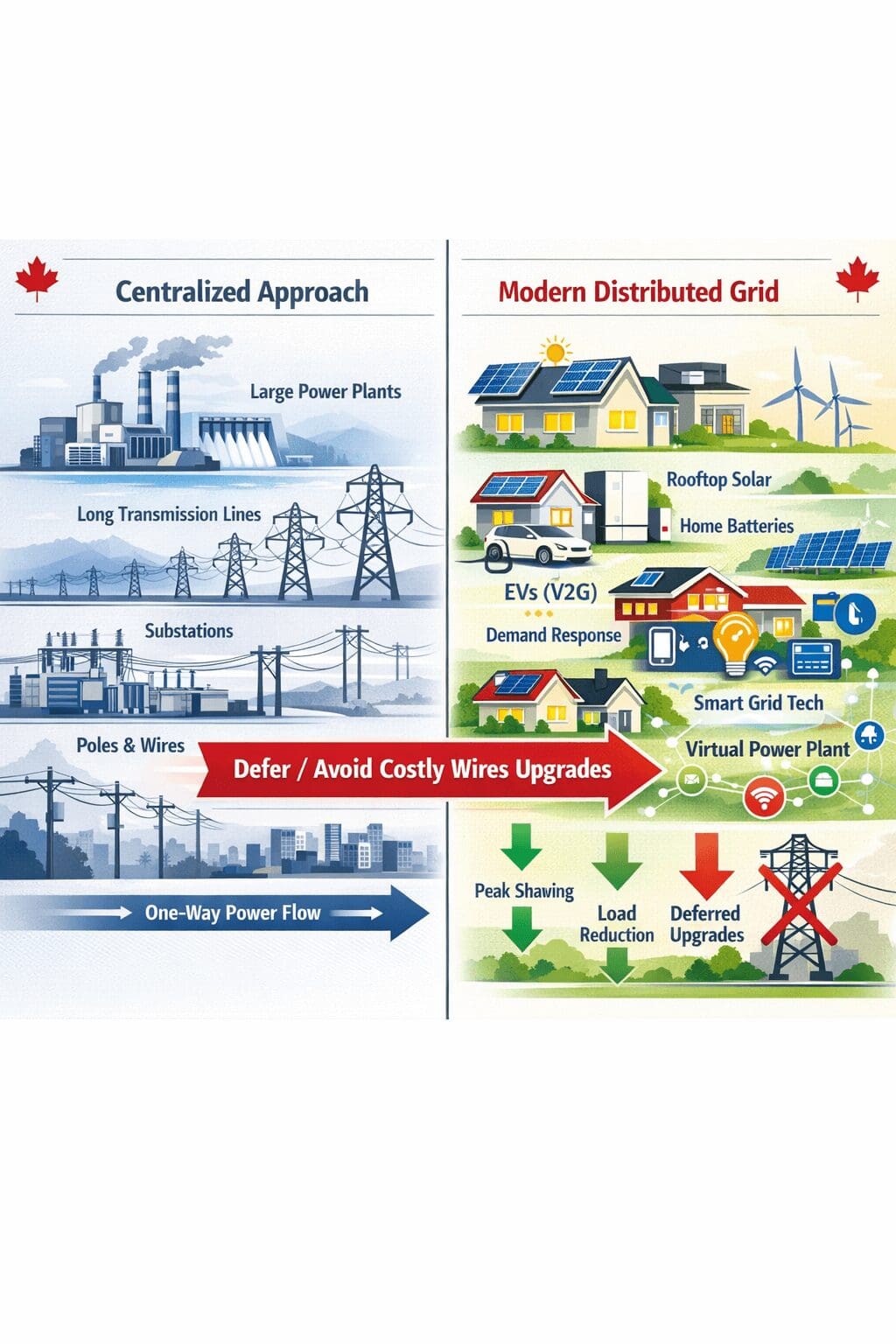

Non-Wires Alternatives (NWAs), also called non-wires solutions or non-transmission alternatives, are exactly what the name implies: smarter ways to fix grid problems without always building expensive new wires, poles, transformers, or substations.

By targeting peak demand with demand response, energy efficiency, distributed generation, battery storage, and smart tech, NWAs reduce load, ease congestion, and resolve constraints. NWAs often deliver the same (or better) reliability at far lower cost than traditional upgrades.

This isn’t just incremental improvement, but rather a fundamental shift in how utilities plan and invest. Driven by plummeting costs for batteries and DERs, surging electrification (EVs, heat pumps, data centers), renewable integration challenges, and the need for extreme weather resilience, NWAs move away from capital-heavy centralized projects toward flexible, localized, customer-involved solutions.

The payoff is that NWAs defer or outright avoid substantial capital investments in infrastructure spend, which in some cases can run into the billions. They offer faster deployment, lower environmental footprint, greater grid flexibility, and more empowered energy users.

As of 2026, NWAs have evolved from niche pilots to a serious consideration in utility toolkits, especially in progressive jurisdictions. In Canada, with intensifying local constraints and a push for cleaner, more resilient systems, they offer a pragmatic way to optimize existing infrastructure, unlock grid-edge value, and build toward a sustainable future without shouldering the full cost of conventional build-outs.

Key Components of NWAs

At the core of NWAs lies a powerful shift in how utilities solve grid challenges. Instead of focusing on large scale centralized power generation linked to load centres through capital-intensive “wires and poles” investments, NWAs focus on a diverse, localized, and often customer-integrated toolkit of distributed energy resources (DERs) and smart demand-side strategies.

These solutions are modular, scalable, and increasingly cost-competitive, especially as battery prices continue to fall, renewable adoption accelerates, and electrification (from EVs to heat pumps and data centers) drives sharper peak loads.

The most common and impactful building blocks of NWA include:

- Energy efficiency programs (e.g., incentives for better insulation, LED lighting, high-efficiency appliances, and HVAC upgrades to deliver permanent, long-term reductions in overall energy consumption).

- Demand response (financial incentives or automated controls that encourage, or in some cases require, customers, businesses, and industries to shift or curtail usage during high-demand periods, effectively creating a “virtual power plant” from the demand side).

- Distributed generation (on-site or community-based renewables such as rooftop or ground-mounted solar PV, small-scale wind, or even combined heat and power systems that generate power close to where it’s consumed).

- Energy storage (battery systems, ranging from behind-the-meter residential/commercial units to front-of-the-meter utility-scale deployments, that charge during low-demand periods and discharge to support peaks, integrate renewables, or provide ancillary services; this has emerged as one of the most versatile and widely procured NWA tools in recent years).

- Microgrids and advanced smart grid technologies (localized networks that can operate independently or in tandem with the main grid, often incorporating controls, sensors, and automation for enhanced resilience and flexibility).

- Load management tools, innovative rate designs (e.g., time-of-use or dynamic pricing), and niche options like thermal energy storage or vehicle-to-grid (V2G) capabilities from electric vehicles.

The overarching goal is to strategically manage or reduce load in specific, high-need grid locations, such as a congested substation, feeder, or circuits, to reliably defer (often by 5–20+ years) or eliminate the need for expensive conventional infrastructure upgrades. Additionally, NWAs typically align with decarbonization targets and support a more distributed, intelligent energy future.

In many regions, portfolios combining several of these elements (especially storage plus demand response plus efficiency) have proven the most effective and economical path forward.

Why NWA Are Gaining Traction

Today, NWAs have moved from promising concept to essential strategy, propelled by a confluence of economic, technological, environmental, and operational realities that make traditional grid expansions increasingly impractical. Plummeting costs for key technologies, particularly lithium-ion batteries, which continue to deliver record-low prices while performance improves, have tipped the scales decisively in favor of localized, flexible solutions. What once required massive upfront capital for new substations or lines can now often be addressed more affordably through targeted energy storage, demand response, and efficiency measures, frequently delivering net savings to ratepayers while deferring or avoiding billions in infrastructure spending.

Electrification and surging demand are accelerating the urgency. The explosive growth of electric vehicles, heat pumps, industrial electrification, and especially AI-driven data centers is creating sharp, localized peak loads and grid constraints that outpace the pace of conventional build-outs. Data centers, in particular, are driving unprecedented power needs (often equivalent to small cities) with interconnection queues stretching years and traditional upgrades proving too slow and expensive. NWAs provide a faster path. Batteries and flexible demand can bridge gaps, smooth peaks, and even enable quicker interconnections by demonstrating load management capabilities, all while enhancing overall grid resilience against extreme weather and volatility.

Beyond economics and speed, NWAs align powerfully with broader societal and policy goals. They facilitate deeper integration of renewables by managing intermittency, reduce reliance on fossil-fuel peaker plants (cutting emissions and local air pollution), and promote equity by empowering customers through incentives, smart rates, or behind-the-meter resources to actively participate in grid solutions.

NWA Deployment Successes

NWA have been deployed successfully across the United States (and in limited cases in Canada), with leading utilities demonstrating that portfolios of distributed energy resources (DERs), demand response, energy efficiency, and storage can reliably defer or avoid massive traditional infrastructure costs while maintaining grid reliability. The following are some of the most prominent and well-documented examples, many of which have influenced broader policy and adoption.

Con Edison’s Brooklyn-Queens Demand Management (BQDM) Program (New York)

This is widely regarded as the pioneering large-scale NWA success story. Launched around 2014–2015 under New York’s Reforming the Energy Vision (REV) initiative, the program addressed projected overloads at substations in Brooklyn and Queens, where load growth threatened a ~$1 billion traditional upgrade (new substations, feeders, and switching stations). Instead, Con Edison invested about $200 million in a mix of customer-side and utility-sited resources, including energy efficiency incentives (e.g., free upgrades for commercial customers), demand response, rooftop solar, combined heat and power (CHP), fuel cells, and energy storage (including a notable microgrid at Marcus Garvey apartments with battery, fuel cell, and solar). The effort achieved over 50–100 MW of peak load reduction (depending on metrics and extensions), deferred major infrastructure for years (with indefinite extensions approved), and delivered projected net benefits in the hundreds of millions through avoided costs, rate moderation, and emissions reductions. It has become a benchmark, proving NWAs can scale in dense urban areas and paving the way for similar programs statewide.

Southern California Edison (SCE) Projects (California)

California has been a hotbed for NWAs, with SCE implementing multiple initiatives through the state’s distribution investment deferral framework and preferred resources pilots. Examples include the Distribution Energy Storage Integration (DESI) project in Orange County (utility-scale storage to address local constraints) and the Distributed Energy Storage Virtual Power Plant (VPP) in the Los Angeles area, aggregating batteries and other DERs for peak management and renewable integration. These have helped defer upgrades amid load growth, nuclear retirements, and Aliso Canyon gas storage issues, contributing to California’s projection that NWAs could meet over 20% of certain infrastructure needs in periods like 2021–2026. PG&E has similarly deployed portfolios addressing localized pockets, emphasizing demand response and efficiency.

Canadian and International Developments

While the United States remains the most mature market for large-scale NWA deployment, Canada has made notable progress in recent years, with several utilities and regulators advancing demand-side and distributed solutions to defer traditional grid investments. These more recent examples help modernize earlier Canadian case studies and demonstrate growing policy alignment with NWA principles.

British Columbia – BC Hydro

BC Hydro’s 2025 Energy Efficiency Plan explicitly positions demand-side resources as a capacity tool, targeting approximately 400 MW of capacity savings by 2030 through demand response, time-of-use rates, and geographically targeted programs designed to defer substation and feeder upgrades. The utility has expanded incentives for behind-the-meter batteries, smart EV chargers, and load-shifting technologies, and now reports over 130,000 participants enrolled in peak-saving programs. These initiatives reflect a shift toward location-specific NWAs, particularly in fast-growing or constrained regions, rather than relying solely on bulk system expansion.

Quebec – Hydro-Québec

Hydro-Québec has emerged as a global leader in residential-scale flexible demand through its Hilo smart home platform and Rate Flex D. By the winter of 2024–2025, more than 400,000 households were enrolled, delivering approximately 2,330 MW of flexible winter peak capacity via automated control of thermostats, water heaters, and EV chargers. Importantly, Quebec’s Bill 69 (2025) now mandates integrated resource planning that explicitly includes demand-side and distributed resources, strengthening the institutional foundation for NWAs as substitutes for generation and network investments.

Alberta – Market Modernization and AI-Enabled NWAs

Beyond earlier studies focused on EV load impacts, Alberta’s policy framework has evolved significantly. The Electricity Statutes (Modernizing Alberta’s Electricity Grid) Amendment Act expanded the Alberta Electric System Operator’s (AESO) ability to procure non-wires alternatives, including energy storage and flexible demand, as part of system planning and reliability solutions. At the technology level, platforms such as BluWave-ai’s EV Everywhere demonstrate how AI-orchestrated EV charging curtailment can manage peak demand at a fraction of the cost of traditional assets, reportedly over 50× more capital-efficient than utility-scale batteries for peak management. These approaches are particularly relevant in Alberta’s deregulated market, where rapid EV adoption, electrification, and data center growth are placing new stresses on local infrastructure.

Why This Matters

Taken together with the US examples, these Canadian developments demonstrate that when deployed in the right locations, NWA solutions can defer or avoid infrastructure expansion, lower system risk, and deliver meaningful savings to ratepayers, all while preserving reliability in the face of rapid electrification.

NWA Global Market

The global market for NWAs and related DERs is experiencing rapid expansion, driven by technological advancements and policy support for grid modernization. Recent estimates indicate that the NWA-enabling technologies, such as energy storage and demand response, are part of a broader DER market projected to grow significantly. For context, while direct NWA market sizing is emerging, aligned sectors like renewable energy integration (which heavily rely on NWAs) were valued at approximately USD 1.14 trillion in 2023, with projections to reach USD 5.62 trillion by 2033 at a CAGR of 17.3%. This growth reflects increasing investments in flexible, non-traditional solutions to address grid constraints worldwide.

In the U.S., NWAs are increasingly integrated into grid planning, with California projecting that they could meet over 20% of certain infrastructure needs during the 2021–2026 period through frameworks like the Distribution Investment Deferral Framework. Similar forecasts for Canada are emerging; for instance, national models indicate NWAs could contribute to saving over $20 billion in total energy-related costs by 2050 in a net-zero economy, by optimizing existing assets and reducing the need for new build-outs. In provinces like Ontario, pilots have shown DERs (key to NWAs) reducing peak demand by 15 MW with net-positive economics, suggesting comparable potential for Alberta amid its deregulated market and rising loads.

Challenges and Barriers Section

In Canada, utilities often face incentives skewed toward capital-intensive projects, due to the prevailing regulatory framework known as rate-of-return (ROR) regulation. Under ROR, utilities can charge customers for their day-to-day operating costs (like staff, fuel, and repairs), plus earn a profit (guaranteed return of ~8–10% depending on the province and proceeding) on money spent building or buying physical infrastructure, like power lines, poles, substations, and other equipment.

As a result, utilities have a financial incentive to prefer large-scale “wires and poles” upgrades over more flexible, lower-cost NWAs, even when the latter could deliver equivalent or superior reliability and grid outcomes at reduced total system cost. This bias can lead to over-investment in traditional infrastructure, higher ratepayer burdens, and slower adoption of innovative, distributed solutions like DERs.

This dynamic is particularly relevant amid rapid load growth from EVs, data centers, and renewables. Recent discussions highlight the need for policy reforms to level the playing field, such as:

- Allowing utilities to capitalize SaaS expenses (software-as-a-service tools for NWA orchestration or grid management) into the rate base, treating them like capital investments eligible for a return.

- Lowering market participation thresholds (e.g., to 100 kW, aligning with U.S. FERC standards) to enable more aggregated DERs and third-party providers to compete in local markets.

These changes would help mitigate the CapEx bias by making operational or hybrid NWA solutions more financially attractive to utilities.

Overall, while NWAs offer clear economic, environmental, and resilience advantages, the entrenched CapEx bias in ROR regulation remains a key barrier to widespread adoption in Canada. Ongoing reforms, such as those in Alberta’s evolving market design and Ontario’s DER-focused incentives, are critical to aligning utility incentives with broader goals of affordability, decarbonization, and grid modernization.

Future Outlook and Policy Recommendations

As NWAs continue to evolve, the future of grid management lies in their deeper integration with advanced technologies, global innovations, and supportive policies. By 2030 and beyond, NWAs are poised to become indispensable for addressing escalating demands from electrification, renewables, and data centers, while enhancing grid resilience and affordability. Emerging trends emphasize hybrid systems, AI-driven optimization, and regulatory reforms that prioritize flexibility and customer participation. In Canada, targeted policy recommendations can accelerate adoption, ensuring NWAs complement traditional infrastructure in a net-zero transition.

Integration with AI and Virtual Power Plants (VPPs)

The convergence of NWAs with artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual power plants (VPPs) represents a transformative trend, enabling real-time orchestration of DERs for peak management and grid stability. AI platforms like BluWave-ai are at the forefront, optimizing DERs such as EVs, batteries, and renewables to form VPPs that defer infrastructure upgrades and provide non-wires solutions.

In the U.S. Northeast, ongoing pilots showcase scalable models adaptable to Canada. National Grid’s ConnectedSolutions program, expanded in 2025, aggregates DERs like batteries and thermostats into VPPs, delivering 250 MW of peak-shaving capacity across Massachusetts and New York through multi-technology participation. Similarly, Edo’s collaboration with Piclo in Connecticut’s Flexibility Marketplace pilot integrates commercial buildings into VPPs, combining demand flexibility with third-party software for grid reliability, marking the first U.S. effort of its kind. These AI-enabled VPPs could expand in Canada by 2030, potentially managing 10-20% of peak loads nationally, reducing costs and emissions while empowering customers with incentives.

Policy Recommendations for Canada

To realize NWAs’ potential, targeted reforms are essential. Federally, the 2025 Clean Electricity Strategy provides a foundation, with $60 billion in investments including the Clean Economy Investment Tax Credits (ITCs) and the Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways (SREPs) program supporting 147 projects nationwide. Budget 2025 finalizes the Clean Electricity ITC at 15% (retroactive to April 2024), removing provincial conditions to broaden access for Crown corporations and incentivizing NWAs through DER integration. Recommendations include expanding SREPs to prioritize NWA pilots and allocating $15 million for inter-provincial transmission frameworks to complement federal decarbonization mandates.

In Alberta, reforms under the 2024 Electricity Statutes (Modernizing Alberta’s Electricity Grid) Amendment Act enable the Alberta Electric System Operator (AESO) to competitively procure non-wires services like energy storage, removing prior limitations for broader application. To further incentivize, introduce tariffed-on-bill financing pilots, which allow utilities to recover NWA costs through customer bills without upfront burdens, which mirrors U.S. models. Additionally, align with performance-based regulation (PBR3, 2024-2028) to reward utilities for DSM and NWA outcomes, potentially saving $800 million by 2050 in distribution costs. These changes would level the playing field, fostering third-party DER markets and supporting Alberta’s deregulated environment.

In summary, the future of NWAs is bright, with AI-VPP integration, global pilots, and policy reforms driving adoption. By implementing these recommendations, Canada can save billions, enhance equity, and lead in sustainable energy, all while positioning itself at the forefront of this utility evolution.